When Mike Johnson, the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, finally agreed to call a vote on a foreign aid bill that included military support for Ukraine, he did so in the face of staunch opposition from the right flank of the Republican Party.

Knowing that his job could well be on the line, he explained his conversion using a George W Bush-era neologism, saying that an "axis of evil" involving Russia, China and Iran had formed.

"I believe Xi [Jinping] and Vladimir Putin and Iran really are an axis of evil. I think they're in coordination on this," Mr Johnson said, referring to the leaders of China and Russia.

That phrase, used by George W Bush in his 2002 State of the Union address to refer to Iran, Iraq and North Korea, is clearly back in vogue.

But it was questionable 20 years ago, and similar questions prevail now.

"At the risk of sounding a bit cynical, the whole 'Axis of Evil' narrative is just a good way to sell a few very complex international situations as being important," Oliver Donnelly, a PhD scholar in International Relations at Queen's University Belfast, told RTÉ News.

The foreign aid bill that US President Joe Biden signed into law this week includes almost $61 billion in funding for Ukraine.

It also includes more than $26bn for Israel and humanitarian aid for civilians in conflict zones, including Gaza, and more than $8bn for US allies in the Indo-Pacific region, including Taiwan.

"This supposed axis is a line of best fit that links support for Taiwan, Israel and Ukraine," Mr Donnelly said.

But that is not to say that there isn't something going on. For one thing, Mr Johnson is far from the only one to link Russia, China and Iran.

Even respected Democratic Senator Jeanne Shaheen, a heavyweight member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, has repeatedly tied Russia with China and Iran, but also North Korea.

It is not difficult to see why.

All four countries have been supporting Russia's war in Ukraine in their own way.

Russia has expressed its "deep thanks" to North Korea for what it described as its "unwavering and principled support" in the conflict.

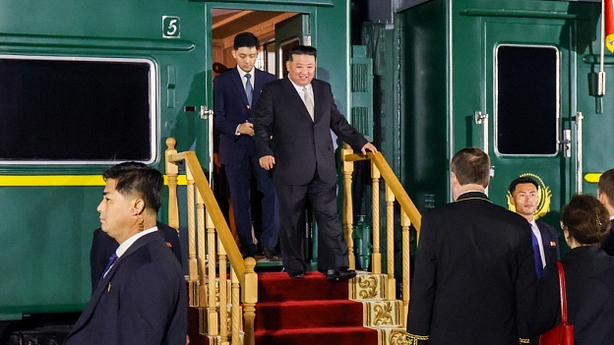

Though both countries have denied it, North Korea is thought to have transferred more than a million pieces of ammunition to Russia since the war began.

Iran's support has been even more pronounced. Though, yet again, both countries have denied it, Russian forces have relied heavily on Iranian drones in Ukraine. More recently, it has sent a huge number of ballistic missiles to Russia.

China's involvement has been more of a balancing act. Though it has not provided Russia with weapons, it has ramped up sales of tools, microelectronics and other components that Moscow needs to manufacture its own weapons.

"Russia would struggle to sustain its assault on Ukraine without China's support," Antony Blinken, the US Secretary of State, said in Beijing on Friday, just hours after meeting Xi Jinping, the Chinese President.

"I made clear that, if China does not address this problem, we will."

Though the historic relationship between China and Russia has been marked by periods of both cooperation and intense strategic rivalry, they have been in alignment now for several decades - more or less since Vladimir Putin came to power in 1999.

But the bond has taken on greater significance since 2014, when Russia invaded the Crimean Peninsula.

After Russia was hit by Western sanctions, China offered crucial financial support and the two countries quickly signed a 30-year, $400 billion gas supply deal.

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022, China has supported Moscow's narrative - that the West and NATO had been threatening Russia.

The common denominator here is Mr Putin's Russia. The question, however, is whether these four countries are actually coordinating in the way the US House Speaker seems to believe they are.

"It's not an alliance yet, but it's certainly a change in international alignments," Angela Stent, a professor of government and foreign service at Georgetown University, told RTÉ News.

"And if you listen to Putin carefully, Russia really does believe that, as a result of the war in Ukraine and now the Israel-Hamas war, there will be a new global order - that the US will be much less important."

Through that lens, Mr Putin believes that these four countries could become the founding members of a new world order.

But the relationships are not exactly harmonious.

For one thing, Beijing is not elated by the rapprochement between Russia and North Korea, since it has always been the main "great power" that has close ties to Pyongyang.

The relationship between Russia and China, meanwhile, is becoming increasingly asymmetrical, in that Moscow is far more dependent on the Chinese than the other way around.

Mr Putin can nevertheless take comfort in the knowledge that China does not want Russia to lose its war.

"What the Chinese really fear would be a regime change there - if Putin was somehow ousted or was no longer there," Prof Stent said.

"They want to have someone in power in Moscow that's going to continue to want to work with China against the world order that they think disregards their interests, which they still see the US as a major player in."

But they also fear instability in Asia as a result of a regime change in Russia.

Whether there is a coherent axis of evil or not, all four countries are acting, from a US point of view, in a way that is contrary to American interests.

There is the threat of a regional war in the Middle East, thanks to Iran. North Korea continues to rachet up tensions on the Korean peninsula, while observers fear that China's posturing on Taiwan is a precursor to some kind of invasion.

"If you put them all together, it's a convenient way of saying, 'we face all of these adversaries and we have to deal with them'," Prof Stent said.

"But I'm not sure. I think people use phrases like 'Axis of Evil', but they're not very precise."

It could also become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

"The more China gets lumped in with Russia, Iran and North Korea, the less they’re going to care about getting lumped in with Russia, Iran and North Korea," Mr Donnelly said.

"There's no coherent axis against the US just yet, but, if I were an American lawmaker worrying about that, I wouldn't be giving them any ideas."