5 years later, how covid has transformed sports and athletes' lives

Sidney Crosby leaned back on the bench at his locker after a practice last month. The Pittsburgh Penguins superstar shook his head with a smile that expressed an almost-disbelieving nostalgia.

Five years to the day from when the previously unfathomable happened, the longtime face of the NHL was marveling at that moment in history when the league abruptly halted its season at the peak of its playoff push — because of a mysterious respiratory virus that shut down the world during the spring of 2020.

“That was just a wild, wild time,” Crosby told TribLive, arms crossed and eyes staring at the locker room’s domed ceiling as he pondered the emotions associated with the covid-19 pandemic.

“It was an experience we all collectively went through that you feel like you should have documented things because it will be so hard to explain down the road. Such a weird, weird time to look back on.”

Every corner of the globe was touched by covid, and the sports world was not immune. It changed financially, and to some degree culturally. The pandemic affected the mental health of athletes in the short- and long-term. It compelled changes — some seismic, some barely noticeable — in the way teams and leagues did business or ran operations.

In a testament to its cultural significance in the United States, it was sports that served as the ultimate bellwether and point of delineation in marking the start of the pandemic in earnest — and the society’s gradual return to normalcy.

“Obviously, there were huge societal concerns connected to the pandemic,” said Jim Andrews, an expert in sports marketing and lecturer at Northwestern. “But if you think about it, a lot of (effort) was spent on, ‘Oh my gosh, how can we get sports back?’ That was a major concern for people. It pointed out how important sports are, just in terms of lifestyle.

“Sports was a big thing that we were missing during covid, in addition to some of the more mainstream things like your job or school. It was, of course, not at that level — but a pretty close second.”

‘Whoa, we really need to take this seriously’

During January 2020, U.S. media outlets began reporting on a peculiar “pneumonia-like illness” that was falling people ill in Wuhan, China. It went largely unnoticed by most Americans, though as the virus spread it gained attention.

Concern was percolating by the time of first reported death related to covid in the U.S. on Feb. 28. By March 8, the BNP Paribas Open in Indian Wells, Calif. — arguably tennis’ most renowned tournament outside of the Grand Slams — was canceled.

Still, tennis generally falls out of the American mainstream. And even as professional, college and high school sports leagues released guidelines and revised policies in response to the novel virus’ arrival in the U.S. — think, handwashing tips and banning reporters from locker rooms — covid was more of a curious inconvenience to most.

The Penguins woke up in their Columbus, Ohio, hotel rooms on the morning of March 11, 2020, a day after a win in New Jersey. When players took to the ice for a 1 p.m. practice at Nationwide Arena, back home some were raising eyebrows at the decision by Mt. Lebanon to forfeit a PIAA boys basketball tournament game out of covid concerns.

Penguins players went through their usual drills, and afterward the primary topic of discussion with reporters (aside from poking fun at the silliness of them being staged 6 feet away) was an untimely penalty taken by Kris Letang the night before.

“I remember that day in Columbus,” Letang said last month. “We had a normal practice. But I kind of knew what was coming. My wife is pretty on top of those things. She was warning me.”

Less than a mile from where the Penguins were practicing, Gov. Mike DeWine at the Ohio Statehouse held a news conference steadfastly urging his state’s residents to stay home. His “advisories” eventually turned into executive orders, by late afternoon March 11 forcing the Blue Jackets’ hand in announcing the game with the Penguins the next day would be played under circumstances then-unthinkable — with no fans on hand.

Still, Ohio at that point was an anomaly. The Penguins announced they would welcome ticketed fans for their next home game four days later. Conference basketball tournaments across the country went on as scheduled March 11, and the clocks began to roll on a full slate of NHL and NBA games that evening.

Then, at 9:32 p.m., things changed. Utah Jazz center Rudy Gobert tested positive for covid, and the NBA soon announced it was suspending its season.

“It was crazy,” Penguins forward Bryan Rust said. “We were sitting in the hotel in Columbus, playing cards, and you hear the NBA canceled its season? We were wondering what the next step was going to be for us.”

The next morning, one-by-one and in quick succession, college and pro leagues across the country called off their seasons/tournaments. The NCAA canceled its crown jewel event, the billion-dollar behemoth that funds the vast majority of virtually everything it does — the men’s basketball tournament.

The only madness that March was a frenzied 24-hour period in which the world of sports came to a screeching halt.

The turning point in covid taking over our collective lives was the decision by NBA commissioner Adam Silver to suddenly pause his multi-billion dollar enterprise.

“To shut down the whole league because one guy had a confirmed case of covid was such a bold move,” said Ted Keith, assistant managing editor at Sports Business Journal. “It just felt like, ‘This is necessary; we are going to do it and damn the consequences.’

“But it had the effect of shocking people. ‘The NBA did what? Whoa, we really need to take this seriously.’ ”

Re-prioritizing life

It was not direct cause-and-effect. But make no mistake, sports shutting down correlated with myriad other industries and walks of life going on pause. If LeBron James and Crosby, the New York Yankees and Kansas Jayhawks, the Olympics and The Masters, are staying home and calling things off, the rest of us recognized this virus was no mere annoyance. It was serious stuff. We needed to stay home, too.

“Sports are such a central focus for a lot of people in their lives,” said Aimee Kimball, a mental skills consultant for athletes at all levels. “That goes for (fans) — but for the athletes themselves, when you put so much time into something, that becomes a big part of who you are. And if it abruptly stops, whether it’s a pandemic or injury, that’s a struggle for anybody. And with covid, there were so many unknown factors that in the short-term created a lot of stress for people.”

Kimball, the CEO of KPEX Consulting, in 2020 was director of player and team development for the New Jersey Devils. She later accompanied Team USA women’s hockey to Beijing as its mental performance coach for the 2022 Olympics.

“The thing with athletes is that they are resilient,” Kimball said. “They have learned how to win and lose and deal with setbacks and things that weren’t fair, so a lot of them were able to apply that mentality that they used within their sport to this major thing that was happening in the world.”

The biggest impact covid left on athletes, according to Kimball, was those who were in college or high school. Scores had eagerly looked forward to senior seasons that never happened. Some had to come to sudden grips that after a lifetime in their sport, their final competitive moments had already happened.

High schoolers who’d been working hard to impress college coaches abruptly had their athletic stages yanked out from under them.

Ancillary negative externalities hit. The NCAA afforded all athletes from canceled or affected seasons an extra year of eligibility. The resulting roster logjam left fewer spots for incoming freshmen.

The adversity of no longer having their sport made athletes ponder if they even really need it anymore.

“Athletes had to decide if this is really something they wanted to stick with,” Kimball said, noting many college athletes declined the offered fifth season. “It got athletes to look at their priorities and really to learn how to cope with stressful and unpredictable situations.”

A time for experimentation

Within a two-week period just after Memorial Day 2020, the NHL, NBA and MLB announced return-to-play plans. Baseball played a significantly reduced schedule. The NBA and NHL opted for a “bubble” format to contest their postseasons.

Professional, college and high school sports would be conspicuously affected by covid deep into 2021. Some aspects of the initial post-covid play won’t be forgotten. Zero (or very few) fans on hand, often with cardboard cutouts or “virtual” fans in their place. Modified schedules to reduce travel. Referees/officials — sometimes, even players — wearing masks. Piped-in crowd noise. Players opting out of seasons or sitting out games following a positive covid test.

By the end of 2021, though, things slowly started to return to “normal.” State and local governments gradually permitted larger gatherings. Leagues reverted to regular scheduling formats. Athletes no longer underwent regular testing.

Some minor rule changes borne out of covid persist — larger practice squads and more liberal flexibility with roster management in the NFL, for example.

Other aspects of sports, though, represent what had been previously viewed as major paradigm shifts. Consider, universal designated hitter or “ghost runners” in extra innings in MLB. Each was instituted out of covid concerns, purportedly temporary. Each, though, stuck.

“(The pandemic) gave a lot of leagues a chance at experimentation,” Keith said during a phone interview. “They had an opportunity to sort of reimagine what they did and could use covid as the excuse.”

The DH was deployed in the National League for the first time in 2020 out of fears that injuries to pitchers would further thin-out rosters already limited because of the virus.

“Remember how much of a fight the DH was every year for 40 years?” Keith said. “It was like a baseball culture war — and then all of a sudden everybody was like, ‘Oh, all right. Fine. Whatever.’ ”

The length of games being a growing topic of consternation, covid likewise gave MLB the pathway to add a runner to second base at the start of every extra inning as a way to head off the occasional 18-inning, six-hour slog into the night at an empty ballpark during a global health crisis. That rule change would have been far too radical for commissioner Rob Manfred to implement at any other time than 2020. But today, “ghost runners” live on.

Similarly, major sports’ flirtations into the realm of streaming had been cautious, so as not to upset a viewing public long accustomed to consuming sports via their cable boxes and over-the-air.

“We all knew that streaming was coming, right?” Andrews said. “But everything was accelerated by the pandemic.”

When covid struck, most live broadcast events disappeared. Production of new scripted series halted. Stuck at home, bored people “binge-watched” shows. Even though Netflix had already grabbed a major slice of the TV-viewing pie, streaming became even more second-nature during covid.

This pushed up the sports world’s timeline that has since led to far more games broadcast on services. Netflix’s Christmas Day 2024 NFL doubleheader that featured the Steelers is a prime example.

“The viewing habits that changed during the pandemic,” Keith said, “gave (league and college conference executives) an opportunity to say, ‘If they are already watching The Tiger King on a streaming platform, maybe they would like to watch the LSU Tigers or the Detroit Tigers.’ ”

Lives altered

When covid first struck, players on pro sports teams scattered back to their homes. Coaching and strength/conditioning staffs communicated with players via the newly ubiquitous Zoom technology as players adapted their training using whatever equipment they could access during the lockdown.

The normalization of video conferencing endures today in the way players train in the offseason under guidance from team staff. It also revolutionized the way pro and college teams scout and recruit players.

Venues, too, adapted. Electronic ticketing had already taken over from traditional paper entry into sporting events, but covid put the final nail in the coffin for almost anything that isn’t touchless. All of Pittsburgh’s major sports arenas and stadiums are now cashless. In lieu of paper identification/credentials, facial recognition kiosks are increasingly used for security.

From ‘swimming in money’ to none of it

Total revenues, franchise valuations and player salaries in the major sports had reliably skyrocketed in recent decades. In seemingly an instant, because of the virus, the endless spigot of money turned dry.

“Sports is an industry,” Keith of SBJ said, “that is kind of swimming in money in which there is always avenues to bring in more. Then, suddenly there was no money at all coming in.”

For close to a full calendar year, major U.S. leagues played on with only a tiny fraction of their typical league-wide annual ticket sales. Monies from parking and concessions disappeared, too. And what about in-venue advertising?

“It definitely changed a little bit of the dynamic between the corporate sponsors and advertisers and the (teams/leagues),” Andrews, the Northwestern University expert, told TribLive.

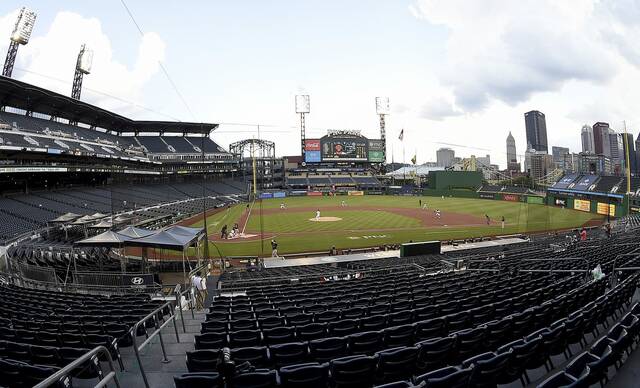

“They had go to in and say, ‘We had a contract where we were going to have a sign at PNC Park for all of 2020, and that’s now not happening. How are you going to make us whole?’ ”

In response, the sports industry eschewed longtime taboos regarding advertising. Covid opened up the floodgates in regards to ad placement in previously sanctified areas.

“Major League Baseball was always pretty conservative about where they were going to allow corporate signage,” Keith, the sports business journalist, said to TribLive.

“But then when covid happened it was like, “Why don’t we put an ad on either side of the foul lines? We have to do something (to make money). Why don’t we put an ad on the pitcher’s mound? Batting helmets? Even ads on jerseys?’ ”

Those latter two ideas had to be approved by players’ unions.

“Teams were basically — credibly, for once — able to say they were losing money,” Keith said. “… There was a lot of money left on the table, so you had to re-work contracts. You had to get creative in some of the things you had to do.”

In most cities, it wasn’t until after the distributions of vaccines during spring 2021 that a gradual re-opening came to sports venues. More than a calendar year without fans put quite the dent in teams’ finances. Salary caps in the NFL, NHL and NBA are set as a ratio of league revenues. To avoid dramatic drops in their respective seasons after the heart of the pandemic, each league had to collaborate with its players’ union to “smooth out” a drop in the cap and provide for a more gradual ramping back up to “normal.”

That was just one example of a cooperative dynamic between American pro sports leagues’ players and owners, two groups that sometimes can have a contentious relationship.

“There was a pretty good spirit of, ‘Hey we need to come together on this,’ because no one could prepare for it,” Keith said.

“It’s actually kind of heartwarming almost. ‘Oh, so you guys can actually come together for common-sense solutions here.’ ”

Total revenues for the four major U.S. pro leagues by now have zoomed far past pre-pandemic levels.

“It shows how much money there is in this industry,” said Andrews, who is a Mt. Lebanon native. “There was cushion there to absorb a huge blow like (covid). Other industries, you didn’t have that. You saw a percentage of businesses that had to close and never come back. The sports economy, there’s so many hundreds of billions of dollars wrapped up in that that there literally was the ability to absorb just a huge body blow and come back very, very quickly. It speaks to the economic power of sport.”

Part of history

It needs remembered that some around the world lost their lives or lost loved ones, and those involved in sports certainly recognize that trumps the stressors they encountered. But now that the pandemic is increasingly retreating into the past, the covid era is something athletes know they’ll be relating to their grandchildren.

“That era of history — what was it like?” Rust said. “What was it like being in the NHL and being in the world at that time? We have all sorts of stories.”

Not unlike when President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave baseball his blessing to play on during World War II, or the unforgettable first pitch thrown by then-president George W. Bush before Game 1 of the 2001 World Series in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the sports world played a high-profile role in lifting national morale during the covid crisis.

It was sports that initially jolted people into attention about the virus — and it also was what most helped let everyone know things were going to be OK.

It directly even aided in that quest. Consider how early in the pandemic New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft lent the team plane for a trip to China to pick up 1.2 million N95 masks. Or how leading sports apparel company Fanatics shifted from making uniforms to manufacturing more than 1 million masks.

“That pandemic affected a lot of families and certainly disrupted everybody’s lives,” Penguins coach Mike Sullivan recently said to TribLive. “I hope I don’t see that again in my lifetime; I am probably stating the obvious there. But the biggest takeaway for me is some of the things we take for granted every day, when it gets taken away from you, it certainly gives you the gift of perspective. Maybe we should take a step back sometimes and just be grateful for what we have.

“Having gone through that time, that perspective should serve us well moving forward.”

Chris Adamski is a TribLive reporter who has covered primarily the Pittsburgh Steelers since 2014 following two seasons on the Penn State football beat. A Western Pennsylvania native, he joined the Trib in 2012 after spending a decade covering Pittsburgh sports for other outlets. He can be reached at cadamski@triblive.com.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.