ISIS is on the ropes in Syria. A successful transition in Damascus could deliver a knockout blow

For much of the past two decades, the Islamic State (ISIS) has enjoyed favorable conditions in Syria, but since the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024, dynamics have changed. With Assad’s departure, ISIS lost its long-standing and vitally important safe haven in Syria’s central desert and its most significant driver for recruitment. The results — so far — have been dramatic.

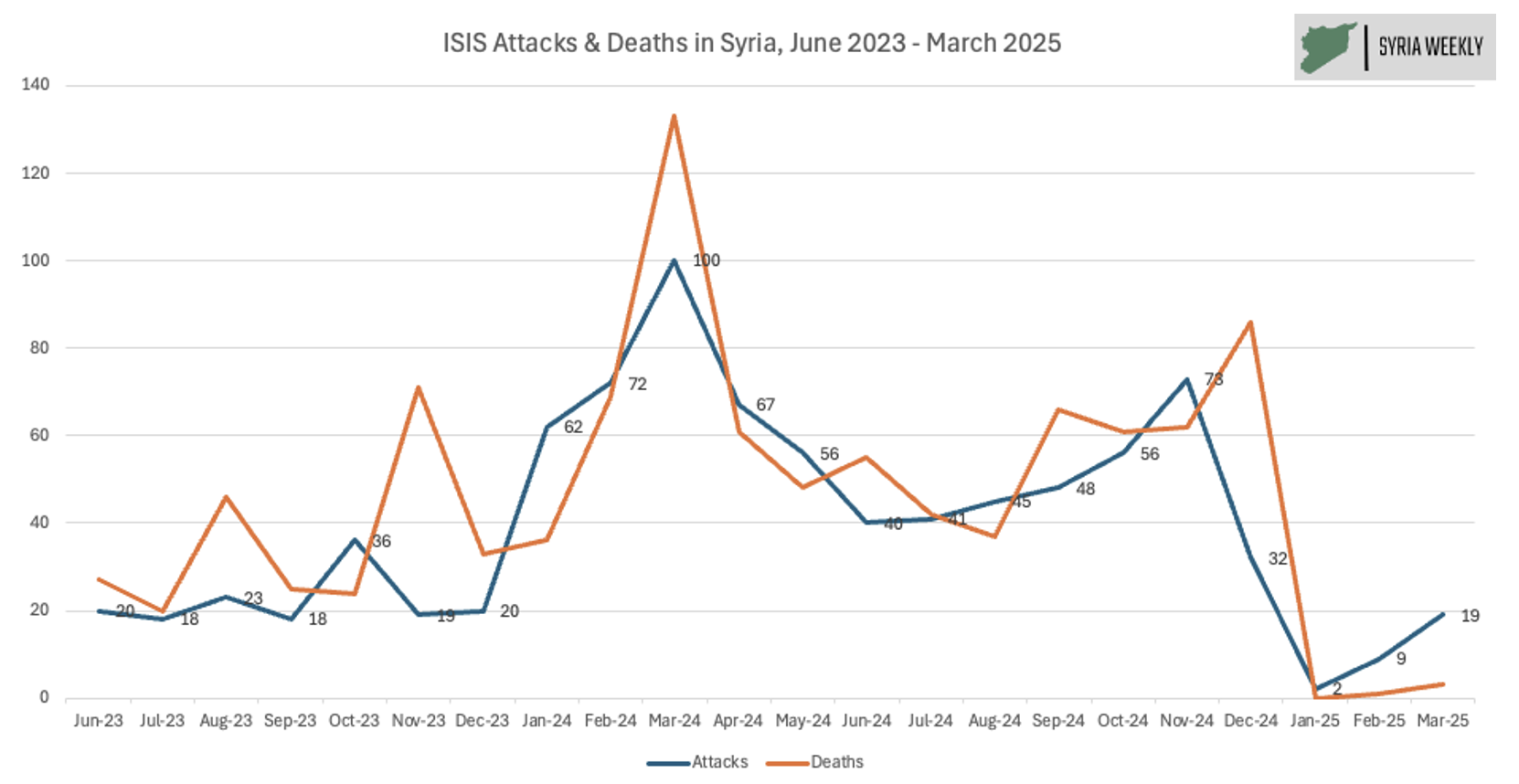

In 2024, ISIS was resurgent in Syria, conducting an average of 59 attacks per month, but since Assad’s departure on Dec. 8, 2024, its operational tempo has fallen by 80% — to just 12 attacks per month, on average. Even more significantly, the deadliness of ISIS’s attacks has plunged by 97% — from an average of 63 killed per month under Assad in 2024 to just 2 per month since then.

There are several reasons for this dramatic change, all of which relate to new dynamics that came into play when Assad’s regime fell. These changes will prove fleeting, however, if Syria’s new reality is not managed well. Ultimately, ISIS’s durable defeat will come about only if Syria’s transition succeeds — with the formation of a government that represents all of the country’s rich diversity; with an economy that is given air to breathe through sanctions relief, substantial investment, infrastructure rehabilitation, and reconstruction; and with the gradual demobilization of a society over-militarized by nearly 14 years of brutal civil conflict.

If these key facets of Syria’s post-war recovery fail to develop, the ingredients for a renewed ISIS resurgence will return once again. Four months into Syria’s extraordinarily fragile transition, there are already signs that ISIS may be on a road to recovery yet again.

Changing dynamics reshape US-SDF partnership

As Assad fled to Moscow on Dec. 8, 2024, US aircraft took to the skies and launched at least 75 strikes on ISIS’s expansive training camp infrastructure in Syria’s central desert. Despite having been responsible for this expanse of territory since early 2017, Assad’s regime had proven both incapable and unwilling to exert real and sustained control. For Assad and his Russian and Iranian backers, the war with Syria’s mainstream opposition was a far greater priority. Having dealt ISIS’s “state” a territorial defeat in early 2019, the US-led coalition was forced to watch as the group’s remnants gradually recovered and rebuilt themselves across the Euphrates River — shielded by a bilateral US-Russian deconfliction agreement that blocked US action in Assad-administered areas.

With that problematic dynamic in play, the disadvantages of the US partnership with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) also began to emerge in recent years. While the SDF has proven to be nothing but a determined, capable, and loyal partner in the fight against ISIS, the dominant role played by its Kurdish components has detracted from the SDF’s ability to turn tactical military gains into a strategic victory. In the core Sunni Arab regions of northeastern Syria (southern Hasakeh, southern Raqqa, and Deir ez-Zour), the sociopolitical ideology of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) that shapes the governance policies of the SDF’s “Autonomous Administration” has fueled increasing discontent. That created openings for Assad’s regime and Iran to instigate tribal uprisings, but it also served to animate ISIS’s local narratives and drive recruitment.

When Assad’s regime fell, the SDF’s political agenda took a big hit, turning overnight from an alternative to brutal regime rule to a widely perceived problem, “occupying” a third of Syria and most of its valuable natural resources. Despite the many considerable complications presented by a post-Assad transition being run by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), Syrians across the country now overwhelmingly expect Syria to reunify behind a transitional government in Damascus. The SDF’s demands for decentralization and federalism raise acute concerns for most Syrians, who have long feared the breakup of the country more than almost any other structural concern.

Having spent the past decade being overwhelmingly — and at times, almost blindly — loyal to the SDF’s agenda, the US military has been impressively swift to adapt to Syria’s new conditions. The commander of the counter-ISIS coalition, Maj. Gen. Kevin Leahy, has played an instrumental role in engaging with Syria’s new authorities, building a working relationship with them and forcing the SDF to the table to negotiate with Damascus. The framework agreement signed by Syria’s transitional President Ahmed al-Sharaa and SDF leader Mazloum Abdi on March 10 came about thanks to an in-person visit by US Central Command (CENTCOM) Commander Gen. Michael E. Kurilla on March 7 and a strong last-minute push by Maj. Gen. Leahy.

According to high-level meetings at the Pentagon and CENTCOM, America’s overarching priority in Syria now is to ensure that the transition underway in Damascus stabilizes and that the new government achieves a monopoly over the use of force. This places the onus on the SDF to make a deal and to display a considerably greater level of flexibility than it has traditionally shown in talks with Syria’s opposition or any government in Damascus.

Already, this is beginning to bear fruit. Beyond the framework agreement signed in March, the SDF has now also withdrawn its military forces from Aleppo city, and from the strategically sensitive front line at the Tishreen Dam — again with CENTCOM playing a key mediating role. Committees from the Syrian government and the SDF are meeting to plan out the next phases of reconciliation and integration, including the SDF’s disengagement from additional areas in eastern Aleppo, such as Deir Hafer, Markadeh, and the Qara Qozak Bridge on the Euphrates. The SDF has also resumed the transfer of oil to Damascus, and talks are underway to see Syria’s transitional government assume control of the network of oil fields located throughout SDF territory. These are vitally important moves in the right direction, in reducing tensions between the SDF and Damascus and building confidence for a more substantive deal that would integrate SDF areas back into the Syrian state.

Establishing ties with Damascus

While pushing the SDF toward Damascus, the US military and intelligence community has also established productive military and counterterrorism ties with Syria’s new government. In addition to Maj. Gen. Leahy’s first meeting with Sharaa in December 2024, the US military also pushed for its other Syrian partner, the Syrian Free Army (based in the al-Tanf Garrison), to formally join the new Syrian Ministry of Defense in January 2025. Its fighters continue to receive US military training, while patrolling deep into Syria’s central desert, around areas like Palmyra and al-Sukhna. In other words, the US now has a partner force operating within Syria’s transitional government.

The US-led coalition is currently in near-daily communication with Syria’s Ministry of Defense, to deconflict and coordinate patrols, aircraft sorties, and counter-ISIS operations. An intelligence-sharing relationship has also been established, which has borne significant fruit. At least nine ISIS plots to conduct mass casualty attacks in Damascus have been foiled by Syria’s Ministry of the Interior since January — mostly thanks to intelligence shared by the US. A string of US drone strikes targeting al-Qaeda operatives in Idlib in February were down to intelligence shared by Damascus. And when Syrian government forces captured senior ISIS commander Abu al-Harith al-Iraqi in mid-February, intelligence gleaned from his interrogation led directly to the joint US-Iraqi killing of ISIS’s number two, Abdullah Makki al-Rifai (Abu Khadija), a month later.

It is within this context that ISIS’s ability to exert itself as it did in 2024 has sharply declined. However, a determinedly resurgent ISIS does not simply disappear into defeat overnight. The group conducted two attacks in Syria in January, nine in February, and 19 in March. In the first two weeks of April, ISIS conducted at least 14 attacks, placing it on course for a fourth month-on-month increase in operations. To prevent the group from recovering to where it was six months ago, the US retains significant responsibilities — and opportunities.

With an enhanced 2,000-troop deployment and a marked decline in hostilities and tensions between Turkey and its Syrian proxies on the one hand and the SDF on the other, now is the time to up the ante and root out what remains of ISIS’s covert infrastructure. The majority of this appears to be within SDF-held territory, as just one of the 40 ISIS attacks so far in 2025 has been in government-held areas, west of the Euphrates. Unilateral and partnered operations with the SDF should be intensified, and air assets need to be cleared to strike at detected ISIS targets at the tactical level. The US should also advance fledgling talks with Damascus to establish a cross-Euphrates coordination mechanism to ensure ISIS is unable to exploit differing areas of control to plan, launch, and recover from attacks.

Detainee crisis in northeast Syria

President Donald Trump has made no secret of his desire to disengage from Syria, so the clock may be ticking in terms of our ability to meaningfully press militarily on a newly and likely temporarily vulnerable ISIS. With a potential US withdrawal on the horizon, the US should also double down on its support for an emerging regional security alliance bringing together Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Syria. It will be a multilateral body like this that stands the best chance of coordinating an effective long-term challenge to ISIS, while simultaneously supporting a strong, stable, and militarily capable Syria. It will also prove a vitally important mechanism for managing the persistent detainee crisis in northeast Syria — where approximately 9,500 ISIS fighters and 40,000 associated women and children continue to languish in prisons and secured camps.

Amid Syria’s transition and the profound uncertainty and dynamic shifts underway, conditions inside these prisons and camps have rarely been more sensitive and fragile. According to one senior SDF source, there have already been three significant foiled ISIS plots to attack prisons. Al-Hol remains an acute security concern, but after years of being far more stable, conditions in al-Roj have deteriorated in recent months. A Moroccan girl was viciously killed by female ISIS operatives on March 25; and during April 5-7, the SDF launched a security campaign in the camp, detaining 16 ISIS operatives, seizing weapons, and discovering several “ISIS schools.”

With international attention focused elsewhere, now would be an ideal time for ISIS to launch a major attack on detention facilities in Syria. While the Trump administration’s aid freeze has created considerable uncertainty around funding and resources, repatriations must accelerate. Iraq remains the shining example, having repatriated nearly 4,500 citizens so far in 2025 — more than in all of 2024. But third-country repatriations have plummeted, with just five people returned in 2025 so far (to Austria) — compared to roughly 380 third-country repatriations in 2024, 750 in 2023, 600 in 2022, and 520 in 2021. The Trump administration should ramp up the pressure on governments across the globe to repatriate their citizens, especially if a military withdrawal from Syria is on the cards. Lining up supplementary or replacement sources of security and funding for the prisons and camps should also be a priority.

Beyond the international dynamics of the detainee crisis, the departure of Assad’s regime and the prospect of a centralized and legitimized central government in Damascus eventually taking charge of the prisons and camps actually present opportunities. Whereas the SDF has long sought to exploit the issue to sustain or broaden its international status — by placing diplomatic and sometimes financial conditions on foreign governments to gain access to citizens, thereby slowing the repatriation process significantly — the new government in Damascus will approach the issue with the opposite mindset. It will be determined to demonstrate openness, flexibility, and good behavior.

Assad’s fall also opens up avenues for large-scale Syrian returns. Almost all of the 8,500 Syrians currently in detention originate from areas formerly controlled by Assad’s regime and therefore could not return until recently. However, this local returns process must be coordinated closely with the transitional government. Since January, the SDF has opened the gates of al-Hol to Syrians willing to return to the rest of Syria, but with no prior consultation with Damascus. Such a policy is profoundly irresponsible — and dangerous.

Looking ahead

While the US and its allies focus on Syria’s transition writ large, placing demands and expectations upon the transitional government, they must not lose sight of the reality that no actor stands more determined to drive instability in a post-Assad Syria than ISIS. The fact that it has been behind at least nine plots to kill large numbers in Damascus since January makes that all too clear. Despite its considerable complexity and imperfect nature, Syria’s transition must be engaged, supported, and encouraged in further good directions. If Syria succeeds, ISIS and all other malign actors will be dealt mortal blows.

With Assad gone and regional states stepping up to support Syria’s transition and long road to recovery, the cause for a sustained US military presence on the ground to counter ISIS has reduced significantly. But a premature disengagement would be a serious mistake and diplomatic engagement and economic openings are urgently needed. In this early phase of the transition, the US and its allies and partners have an invaluable opportunity to shape what comes next, including on the security level. Dealing ISIS a truly irreversible blow is now a feasible goal, but it will take more adaptation, more military diplomacy, and a doubling down of efforts on the ground to hit ISIS while it remains vulnerable — and before it regains steam once again.

Charles Lister is a senior fellow and head of the Syria Initiative at the Middle East Institute.

Photo by HUNAR AHMAD/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click here.

Distribution channels: Politics

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release